At the end of October, I had the exciting opportunity to co-facilitate a workshop on Consentful Tech at the 2017 Mozilla Festival in London. Dann Toliver and I wanted to share the content of our recently released zine, “Building Consentful Tech”, while also inviting feedback on the framework we put forward in it and start working on strategies to create a more consentful internet.

Here’s a synopsis of the session!

1 / Welcome & trigger warning

We opened the session by passing out the zines, introducing ourselves, and finding out who was in the room. We had an equivalent number of application developers and designers, as well as several policy people and educators.

We also shared a trigger warning, as discussions of consent are necessarily enmeshed with conversations about violence and rape. We’re so grateful that we had Meghan from Mozilla at our session, who offered to provide support to anyone who required it and connect people to resources should they need them.

2 / Identifying common apps we use

For our first activity, we asked participants to get into pairs and identify an app they both use frequently, along with consent concerns they might have about that app. I find that discovering commonalities is a very useful popular education technique. It starts everyone off on shared common ground while also connecting people with each other’s experiences.

Some apps and the concerns they raised included:

- Map services: my location information is being tracked

- Search engines: my search history is being shared with advertisers

- Messaging apps: I’m forced to share all my contact with the service in order to use it

- Photo sharing services: I can be tagged in a photo without my consent

In the discussion, one participant shared the all-too important point that they, as a deeply technical person, have the ability to build their own phone and ensure their own security, and that this opens up a dangerous gap between those who have this privilege and those who do not.

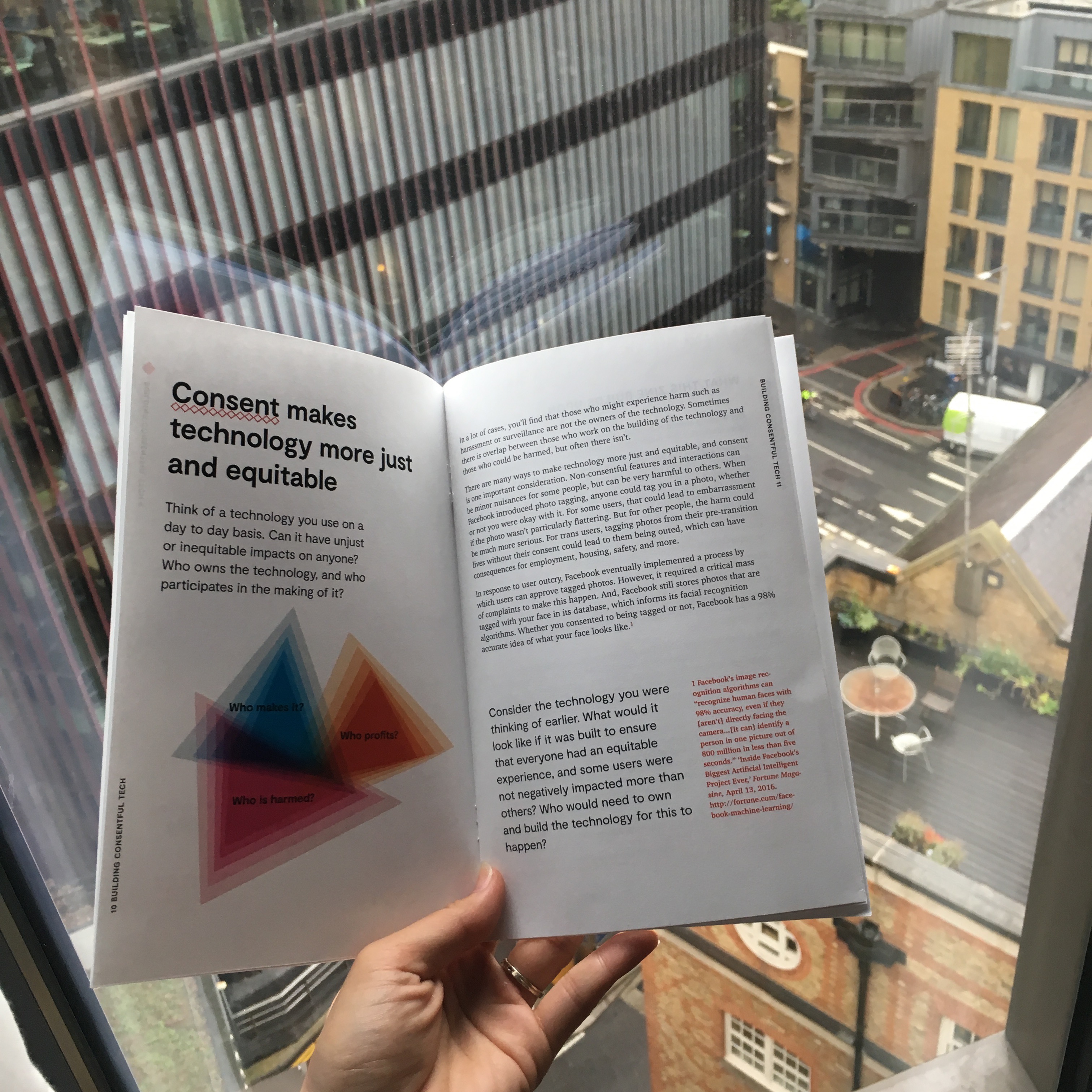

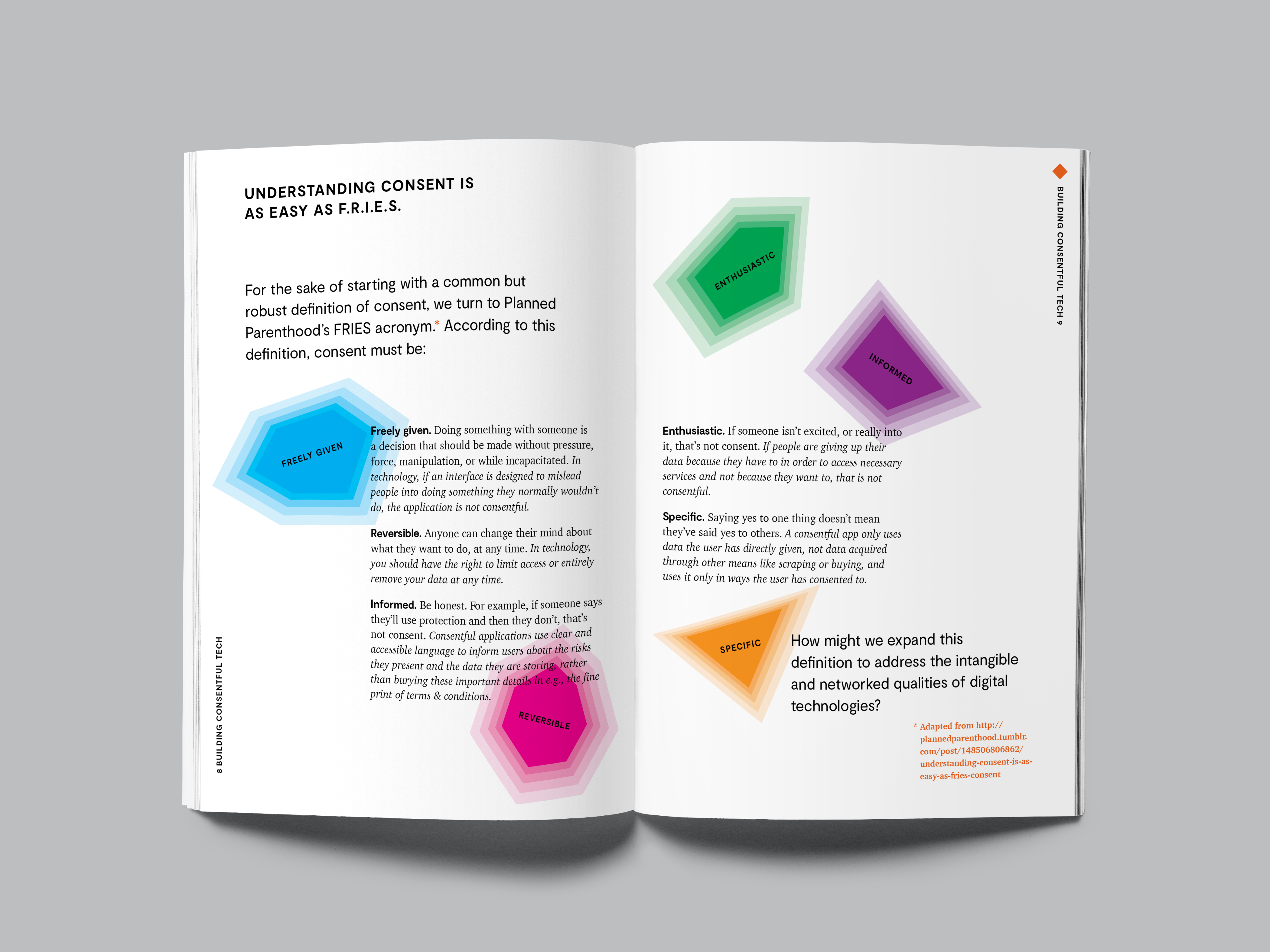

3 / Consent is as simple as FRIES

Next, we opened the zine to the spread that applies Planned Parenthood’s FRIES acronym to technology. According to this framework, consent is:

- Freely Given: Doing something with someone is a decision that should be made without pressure, force, manipulation, or while incapacitated. In technology, if an interface is designed to mislead people into doing something they normally wouldn’t do, the application is not consentful.

- Reversible: Anyone can change their mind about what they want to do, at any time. In technology, you should have the right to limit access or entirely remove your data at any time.

- Informed: Be honest. For example, if someone says they’ll use protection and then they don’t, that’s not consent. Consentful applications use clear and accessible language to inform users about the risks they present and the data they are storing, rather than burying these important details in e.g., the fine print of terms & conditions.

- Enthusiastic: If someone isn’t excited, or really into it, that’s not consent. If people are giving up their data because they have to in order to access necessary services and not because they want to, that is not consentful.

- Specific: Saying yes to one thing doesn’t mean they’ve said yes to others. A consentful app only uses data the user has directly given, not data acquired through other means like scraping or buying, and uses it only in ways the user has consented to.

We invited participants to volunteer to read sections aloud to the group. This is a pop ed technique I learned from Allied Media Projects, as it is supports different types of learners — those who prefer to digest text visually, to hear it aurally, and to read along.

We discussed how this framework might provide some insights into the consent concerns we raised with the applications mentioned in the first activity or if it gave rise to new concerns. Here are some takeaways:

- Freely given: What if we’re trying to access a social service like welfare and we are required to provide sensitive and identifying information? What does this mean for criminalizing people that rely on these services?

- Reversible: We can’t fully revoke access to our data when we want or need to leave a system. How does this impact people who are being stalked? What about trans people who want to un-tag themselves from childhood photos?

- Informed: Terms and conditions are very opaque about how our data is being used and what risks we’re being exposed to. These seem intentionally written to bore and confuse, and the bar is higher for people with learning disabilities.

- Enthusiastic: We can’t seem to avoid social platforms, as many of us are required to use them for work and to maintain relationships. While some of us might have started as curious and enthusiastic users, the scope of data these applications can access continues to widen, and the lack of real alternatives means many users choose to keep their accounts despite growing privacy concerns.

- Specific: Increasingly, our personally identifiable account information is being merged with our browsing history without users specifically agreeing to this kind of tracking. This is especially concerning for people targeted by repressive administrations that can pressure or trade favours with Internet service providers and tech companies.

Participants found that applying Planned Parenthood’s definition of consent to technology and online interactions helped provide more pointed critiques of common applications and highlighted how little we actually consent to in our digital lives.

4 / Digital Bodies

We then shifted to talking about our digital bodies. Participants discussed what our digital bodies are made up of, what we can do with them, and what can be done with them.

Unlike our physical bodies, our digital bodies don’t exist in one centralized location, and are made up of a multitude of bits and pieces. While this provides a lot of neat opportunities for users, it also opens up new ways for our digital bodies to be manipulated and harmed.

We wrapped with a lofty question that we are just starting to ask, nevertheless answer: what if we were in complete control of our digital bodies rather than being required to trust service providers, servers, and companies with our data? What would that Internet look like?

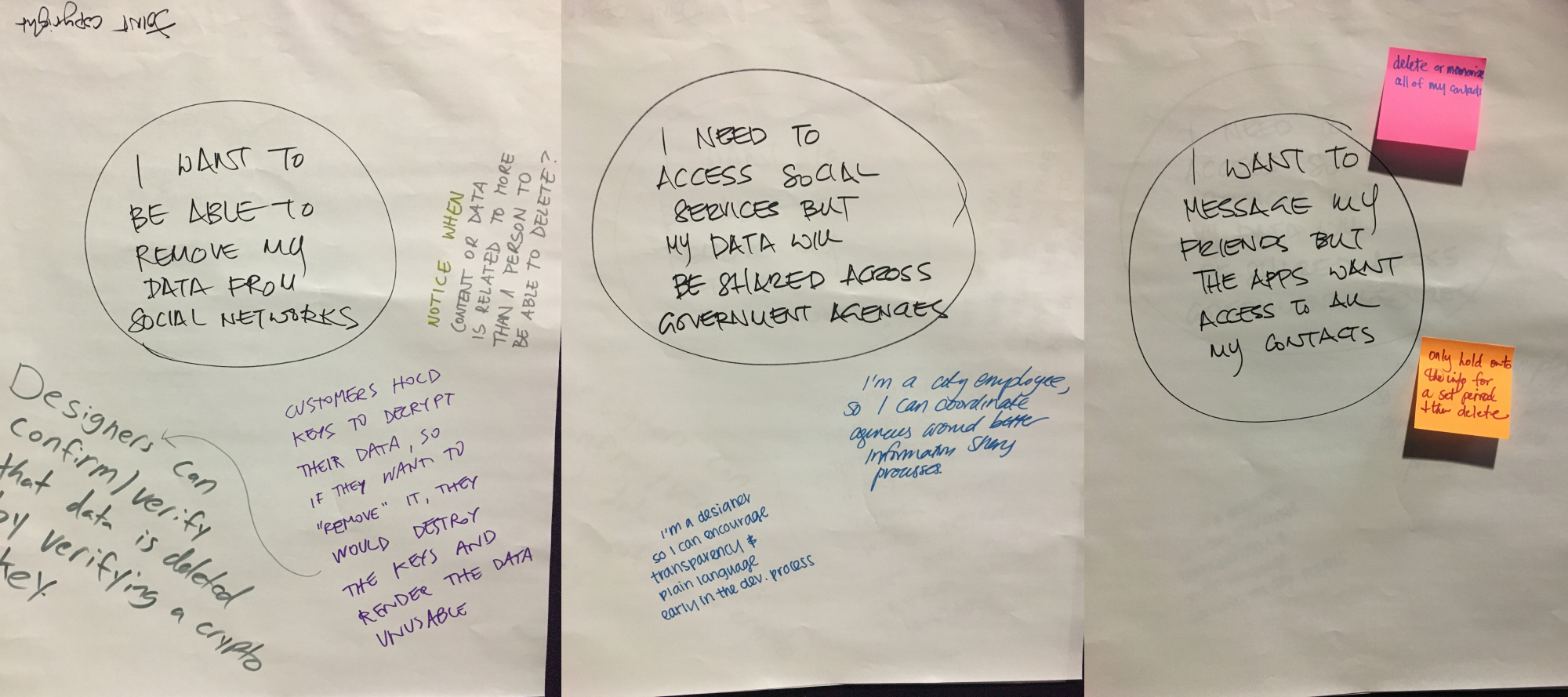

5 / Problem Spaces

In our last activity, we revisited some problem spaces that we discussed at the beginning of the session. We wrote out concerns on giant stickies and broke into smaller groups to strategize around these concerns.

Rather than asking people to just solve the problem however, we asked them to come up with strategies based in their own roles and identities, for example, designers, users, civil servants, educators, etc. By starting where people already have a firm understanding of their agency, we begin to see how each of us has a role to play in making change possible.

“I want to be able to remove my data from social networks.”

- Joint copyright

- Notice when content or data is related to more than a person to be able to delete?

- Customers hold keys to decrypt their data, so if they want to “remove” it, they would destroy the keys and render the data unusable

- Designer can confirm/verify that data is deleted by verifying a crypto key

“I need to access social services but my data will be shared across government agencies.”

- I’m a city employee, so I can coordinate agencies around better information sharing processes.

- I’m a designer so I can encourage transparency & plain language early in the dev. process

“I want to message my friends but the apps want to access all my contacts.”

- Delete or memorize all of my contacts

- Only hold on to the info for a set period then delete

6 / Commitments

We began to run out of time here! But we managed to wrap by acknowledging what we demonstrated in this quick strategy activity: that we can each do something to build a more consentful Internet, and we do not need to — and can’t afford to — wait around for big companies and the Federal Communications Commission to protect our digital bodies. While there’s a lot we can’t control, we shouldn’t lose sight of our agency as users and makers of the Internet who can and must have a say.

We asked folks to commit to tackling these challenges within our respective roles and continue building with us. We hope participants will read the full zine and share feedback here so we can continue to refine this framework. Thank you MozFest!

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.